Winning a Competition without actually winning it

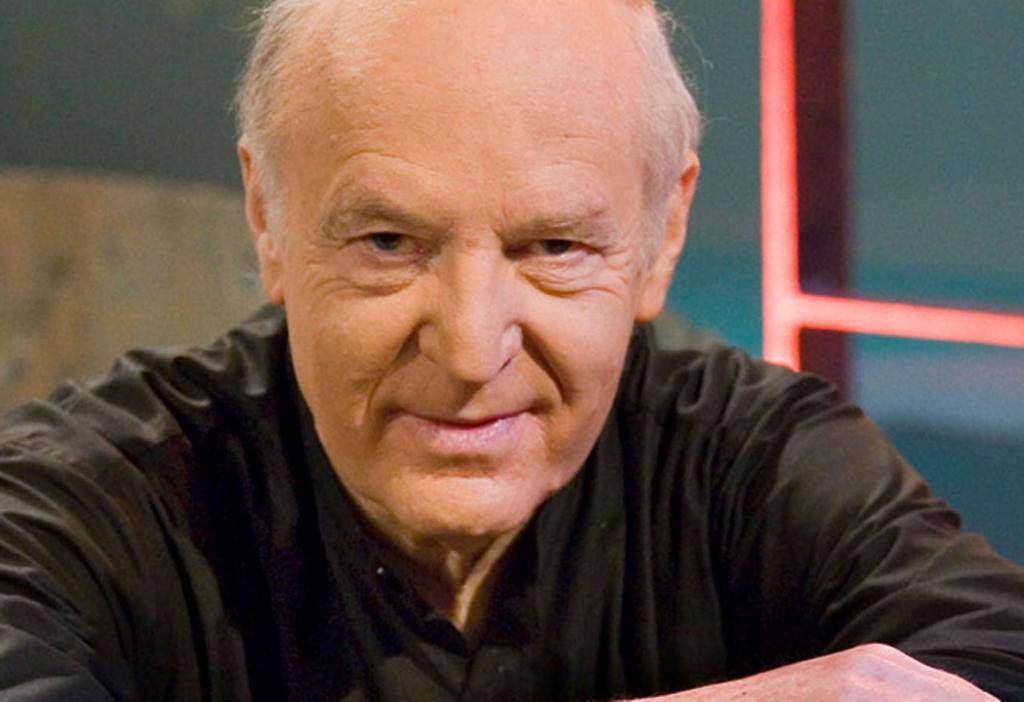

An interview with Arie Vardi, Chair of the jury at the Rubinstein Competition

WFIMC: The last Rubinstein Competition 2 years ago was still quite affected by Covid, but it turned out a huge success...

Arie Vardi: Two years ago we were quite lucky. It was a hybrid competition, partly online, but thanks to Ariel Cohen, who is not only a good musician but also a computer professional, we succeeded to hold the competition on a very high level and the outcome was great! But this year, we are somewhat back to a normal situation.

If you know the Rubinstein Competition, you know that you can define it as „belonging to the public“. From the first round, the public is always there, we have a full house, and very few competitions in the world enjoy this situation. I have been at many rather renown competitions where in the first round the hall was completely empty, and the public started to wake up only towards the end. Here, it´s not only a public competition, but you can really call it a „national competition“ because this is the one and only, Israel is a very musical country, we have good orchestras - two orchestras will take part in the competition- and I believe that this position of a „national competition“ is exactly what we need.

What´s new at the 2023 edition?

We tried something new in every edition. I believe that our competition was always creative and innovative - take things like the „young jury“ which makes the young listeners involved. Letting the public clap between the works and make performances more like a concert, not a competition. Let the contestants play encores to see how they run the show. To look at the competition more as a festival with the presence of a jury- not a competition with the presence of a public.

You called the Rubinstein Competition a „Life experience“. What makes it a life experience for the competitor, aside from what you mentioned?

The competition is not as old as the Chopin, Queen Elisabeth or Geneva Competitions. It´s about same age as the Cliburn and Leeds, so we are not as old as the „veteran competitions“ and not as young as the new competitions. We are middle age, so to speak, but we were privileged with a fantastic jury from the very beginning. The jury of our first edition was really the „secret weapon“ of our competition. Rubinstein came here, he was on the jury, and with him came some of his friends like Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli, Nikita Magaloff, and later Rudolf Firkusny, Jan Ekier, Eugene Istomin, Leon Fleischer, Jacques Fevrier- people you read about only in encyclopedias. But they came here as jury members. They never judged many competitions, but they came for Rubinstein. The starting point was incredible, and later on, we were again privileged to have the best jury in the world, and this jury attracted many contestants.

Also, I believe that one important decision plays a big role: jury cannot have their own students take part. This is very attractive for many young contestants. Of course we also miss some competitors which are students of the jury, because some of the jury are the most renown pedagogues, but on the other hand it makes the competition a lot more attractive. And I must say that in spite the fact that sometimes in the past the competition took place during certain hard periods for Israel in terms of wars and security, we never cancelled we were always blessed with good contestants.

So this combination of excellent jury, top class contestants and winners made the Rubinstein into what it is today. And I also must say that unlike other competitions, I don´t think that we ever missed a good first prize winner. There is no one among the top pianists of the world who came to our competition that you can say we ignored them. Up until now this never happened to us. So this is a good job of the jury and also of the public- the public is very selective, very opinionated. Its like part of a game. Of course we cannot say that the public will influence the jury directly. But you know that a warm atmosphere, a certain electricity in the air, is not only created by the artist on stage, it also comes from a good public. All that, one by one, makes a big difference.

You have been on many juries over the years. What is your recipe to find among those hundreds of applications the top people? The level has become so high, there are no more big differences between excellent and mediocre- everyone plays on a very high level and it has become increasingly difficult to find those with the biggest potential, without dropping any on the side because they are making a mistake or looking funny on the video etc…

This is the Million Dollar Question. I would like to refer- with your permission- to the previous issue we were talking about; the jury. It's not enough to have a high quality jury- the balance, the composition, the „cocktail“ of the jury is essential. Even if you change one jury member, the results could be different. But what makes a good jury member is not only artistic level or life experience but also good taste. You have to choose for the jury people not only professionals who can find mistakes in the urtext, but tasteful people and also artists with clairvoyance who could not only feel the presence but also the future of those young pianists, because some of them are really very young and will still develop.

Another element is the preselection. Unlike other competitions, we don´t do it by video. We just examine the written materials, the portfolio, the documents they send. Of course, the jury of the preselection can listen to youtube clips if they want. But this is not our issue: to give equal chances to those few hundred applicants is simply not possible. You cannot pay equally good attention and for example compare No.87 with No. 172. No jury member can commit to listening to clips for one month, 10 hours a day, and still be able to judge. That´s why we decided to do things differently, based on the experience of the preselection jury.

The jury of the competition is very much dependent on the job of the preselection jury, in order not to miss a good contestant or a potential First Prize winner. We hope we don´t do too many mistakes, and if we do those mistakes, they could be forgiven because they were based on CV and recommendations, but not on playing.

In the competition proper, what also counts is of course the repertoire. Good repertoire could allow the contestant to make the slalom through the different opinions of different juries, and I believe our repertoire is very good and allows for good artistic programs with beginning, middle and ending in each stage. So all this plays a role.

Often it´s impossible to compare competitors. Take Horowitz and Rubinstein, for example, how can you compare them? Who is the better pianist? You cannot answer the question, and in the same manner, sometimes you cannot compare two pianists during a competition. Of course, none of the young pianists are Horowitz or Rubinstein (yet), but still, the comparison is the same. In the end we have to make decisions- sometimes very difficult and dramatic decisions. And this again is the reason why it is so attractive for the public: the audience can see what is going on- what is the difference between their own opinion and the opinion of the jury? Is there Justice? Are there victims? And we can always comfort ourselves that even if there are victims, there is a public. And you can win a competition without actually winning it.

But as you say, today the participants are all playing on a very, very high level, and then the real question is about finding the better artist. The one who can make you laugh and cry, who can touch your heart in the best way…. and this is not so easy.

Maybe we can finish with a look into the past- if I remember it right, you were on the Rubinstein jury for the first time in 1977- it was the second competition…

True. In the first one (in 1974) they still wanted me to compete…

But in any case- you met Rubinstein. What are your memories? What stories do you have to tell of this great pianist?

Not only I met him, I played for him a couple of times. I cannot say I was his student, because nobody can say he was his student. Some people may say so, but… anyway, I played for him, and he was listening in such a wonderful way, then only said one or two words. And it was so very valuable. Sometimes he demonstrated, and those sounds, just one b flat, still ringing in my ears- his personality, his presence, his deep voice… among all the pianists of the past, his style was always up to date. There was no mannerism. There was nothing that you could say belonged to the 19th century or the beginning of the 20th century; something was deja-vu and this style was out of fashion. He was young and fashionable and always in good taste. He was original and individualist, but never obnoxious, never annoying, never too fast or too slow, too loud or too soft. Not only correct, but beautiful and attractive- and vivid. His repertoire was never esoteric. Always mainstream, but interesting mainstream. He could play Mozart without any touch of mannerism, eastern European mannerism, but he could also play Rachmaninov and late romantics, and above all: Chopin. We speak about a style of Chopin playing- it´s amazing.

I met him a few times and I also helped him- he was already blind and could not hear well- you had to speak directly in his ear. But the most touching story was when someone was playing Ballade No. 1 and he said he would like to demonstrate. And so I helped him to the piano, I took his hand and brought him to the bench, but he sat down in the wrong place. It was my mistake, he was too far on the bass side. He was using the soft pedal with his right foot and he played everything one octave lower. The situation was very embarrassing. So I went to him and said: Maestro, sorry that was my mistake, may I help you? And we moved a bit, he looked at me with his wicked smile and said: oh, I am an old fool… So we moved to the right place and he tried to demonstrate Ballade No. 1. Because of the situation, it didn´t work well, and he couldn´t synchronize the right and left hands, and it was very embarrassing again. But he was stubborn, and kept fighting and fighting, trying again and again. And finally- bingo- it went and he started to play, and I can tell you: those were the moments, you know... I am still in tears when I remember that time. It was like somebody from a different world was playing the piano. The sound, the phrasing- quiet on the outside, but so deep on the inside….unforgettable.

Born in Israel, Arie Vardi gave his first recital in Tel Aviv at the age of 15.

He studied at the Tel Aviv Rubin Academy of Music with Neima Rosh and Olina Vincze-Kraus and at the same time completed a law degree at Tel Aviv University. Later he studied piano, composition and conducting with Boulez and Stockhausen. In 1960 he won the Chopin Competition in Israel and made his first appearance with the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra. A year later he won the Enescu Competition in Romania. Since then he has appeared with all the Israeli orchestras, in recitals and chamber music concerts. He has toured Europe, North and South America, Africa, The Far East and Australia, playing under the baton of conductors such as Paul Paray, Zubin Mehta, Kurt Masur, David Zinman, Semyon Bychkov and others.

He regularly appears as conductor and as soloist-conductor. He has served as juror at major international competitions and has recorded for international labels. Several of his records have won awards.

Arie Vardi is a professor at the Hochschule fur Musik in Hanover and at the Buchmann-Mehta School of Music, Tel Aviv University. Over 40 of his students have won first prizes at international competitions. He has created and presented more than 300 television programs, including the "Master Class" series and "Intermezzo with Arik". In 2004 he was awarded the Minister of Education Award for his life achievements.

©WFIMC 2023