The Day Van Cliburn won

A look back at the greatest success of the Cliburn International Piano Competition namesake, Van Cliburn

By Florian Riem

MOSCOW, Monday, April 14 — Van Cliburn, a 23-year-old American, has won the first prize in the Soviet Union's international Tchaikovsky piano competition. Mr. Cliburn, a Southerner who lives in New York, triumphed in what had been regarded as a contest of extremely high standards over three young Soviet pianists and one from Communist China. The awards were voted late last night by a panel of sixteen jurors, including six leading Soviet musicians. Their choice clearly coincided with that of the Moscow public. Muscovites wildly cheered Mr. Cliburn´s performance in the finals Friday night. (The New York Times, 14 April 1958)

Of all the competition wins in history, Van Cliburn winning in Moscow, at the height of the cold war, was arguably the most spectacular and most memorable event. Twenty-three years later, at the semi-finals of the 1981 Van Cliburn Competition, Cliburn himself recalled his Moscow appearances in a New York Times interview: ''When I was 5 years old,'' he said, ''I announced to my family that I wanted to be a concert pianist. My father wanted me to be a doctor, but after I made my debut with the Houston Symphony when I was 12, there was no doubt that my father was going to go along with me. About that time I got a book of pictures about Russia, and I fell in love with St. Basil's Cathedral. When I got off the plane in 1958, the first thing I asked the Russians was if they would take me to Red Square before taking me to the hotel. They were happy. I remember it was snowing, the lights in the square were on, and I stood there transfixed.''

The New York Times article continues: “All of the contestants were housed in the newly opened Peking Hotel. They were given studios at the Moscow Conservatory, where they could practice in shifts. Mr. Cliburn drew a night shift, which he loved, as he was a night person. He never did hear much of the playing of the other contestants. The conservatory walls were thick. He remembers entering the conservatory one night: It was dark inside, with only one spotlight thrown on a bust of Mussorgsky. Looming dimly behind was a portrait of Tchaikovsky. Mr. Cliburn said he stood there and shivered…the place felt like it was full of ghosts.”

In the morning of the first day of the competition, the temperature in Moscow had dropped to minus 17 Celsius. Of the expected 50 pianists, only 36 were present. Besides the four Americans who had made it, the contestants came from Argentina, Bulgaria, Canada, China, Czechoslovakia, Ecuador, France, Hungary, Israel, Japan, Mexico, Poland, Portugal, Romania, the USSR, and West Germany. As for the jury, alongside the legendary Sviatoslav Richter and Emil Gilels, both of them pianists from Odesa, was their famous teacher Heinrich Neuhaus, as well as Lev Oborin, winner of the First Chopin Competition in 1927 and teacher of Vladimir Ashkenazy. Dmitry Kabalevsky and Sir Arthur Bliss (UK) represented the composers. All in all there were 17 judges- 12 from the Soviet Bloc and 5 from elsewhere. Tensions in the jury were running high- not only between the difficult Richter and his colleague Gilels, but also between the pianists and the composers. Neuhaus hated Dmitry Kabalevsky and talked about him as the “poor man´s Prokofiev”, while Richter went even further, calling Kabalevsky “deeply unpleasant” and declaring that it had never occurred to him to play his “threadbare music”.

From early on, it was clear that the competition would be decided by no one else but Khrushchev. As for the Soviet judges, they could only guess what kind of retribution the government would come up with if they denied one of their compatriots the first prize. Richter, on the other hand, could not have cared less. “For me”, he said, “people either make music or not music”, he said and was promptly accused of “individualism”.

“In 1958 the First International Tchaikovsky Competition was announced. Dmitri Shostakovich was named chairman of the steering committee, and the country´s best-known musicians headed up the juries. Students were coached and drilled: word had come down from above that Soviet musicians had to win all the First Prizes. And to that end, everything possible was done. Young musicians who had made it through nationwide competitions were sent to the countryside to spend a few months in separate dachas. They were supplied with free board, cars, and grand pianos for practicing. The best of the professors were obliged to go and work with them. Soviet musicians were trained as if they were cosmonauts. It was a matter of building the communist state´s prestige, of propagandizing the Soviet system” (Galina Vishnevskaya: Galina. A Russian Story, 1984)

Van Cliburn faced many challenges in Moscow, both emotional and physical. He always appeared controlled, easygoing, naïve… yet his behavior, his high-flown American rhetoric, and his somewhat childish ways were also camouflage: an imaginary wall to protect himself from the many discomforts and challenges of suddenly being in the limelight. “He has the psychology of a fourteen-year-old boy” said Sviatoslav Richter, “And thank God!”, Heinrich Neuhaus agreed. Van Cliburn was playful, child-like and often embarrassingly earnest. According to Neuhaus, this linked his personality with Goethe, Tolstoy, Schubert, Tchaikovsky and Rachmaninoff. On the negative side, the press, and especially the American press, was quick to judge and comment on his unsophisticated personality and somewhat lacking social skills. On top of this, his love and admiration of the Russian public became problematic for American politics, setting off alarm bells in Washington. When Cliburn embraced the Russians as “my people” and said he had never felt so at home anywhere else, this verged on treason in the eyes of the State Department.

As the competition progressed, things began to become clearer. Chinese pianist Liu Shi-kun had played well, as had the Russian Lev Vlassenko. Two of the Americans- Van Cliburn and Daniel Pollack- were shining. After the second round, Sviatoslav Richter gave a press conference, claims Pollack- though jury members were actually forbidden to make public statements about the pianists- “and he spoke about my performance of the Prokofiev Seventh Sonata, a piece he had premiered, as being inspired by the devil!” It seemed that by the beginning of the third round, Pollack was ahead of Cliburn. Even the Moscow critic from the magazine “Sovetskaya Kultura” agreed, calling Cliburns performance “uneven”. For many, Cliburn would not have won, was it not for the final. “In the final round, the young American instrumentalist literally staggered both the jury and the audience with his phenomenal gift”, wrote the magazine. And indeed, at the crucial moment of the competition, Cliburn was at the peak of his form.

It was Friday, 11 April 1958. Tchaikovsky Concerto was first, one of the most popular works of its genre, romantic, emotional, stunning. Kirill Kondrashin conducted the Moscow State Symphony (Founded by the government of the USSR in 1943, it is one of the oldest symphony orchestras in Russia and still exists today). The hall was packed to the last seat, with people standing in the aisles and on the stairs. Among the dignitaries in the audience was Queen Elisabeth of Belgium, arguably Europe´s greatest patron of the arts at the time, seated next to Khrushchev´s daughter.

Cliburn hat cut one of his fingers and had to play with a bandage, but this did not diminish the shear overwhelming power and excellence of his playing. The acclaimed Russian pianist Nina Lelchuk, 15 years old at the time, recalls a school janitor weeping during Cliburn´s performance of the second movement of the Tchaikovsky. “He said he never listened to classical music,” she reported, “but that he was so struck by the tenderness he heard in the lullaby-like slow movement of the Tchaikovsky, that he couldn’t control himself”.

Most competitions ask for one romantic concerto in their finals. The Cliburn Intl. Piano Competition asks for two, but schedules them for different days. At the Tchaikovsky, it was two concertos in a row, plus a newly commissioned piece in between. In 1958, that piece was the a-minor Rondo by Dmitry Kabalevsky, an indiscript yet rather demanding 5-minute work for solo piano that is hardly ever played today. During Cliburn´s performance of the Kabalevsky, a piano string snapped, so a technician had to be called in to repair the instrument, while everyone waited.

Rachmaninov was last. According to many eyewitnesses, this performance of the 3rd Piano Concerto was not only outstanding, it changed history. “People would not hear this music again in the same way” writes Stuart Isacoff. Cliburns tempi were slow, his phrasing generous. He seemed perfectly in tune with Kondrashin and the orchestra. Then came the end of the first movement and a stunning surprise: For the first time in living memory Cliburn was playing the “Ossia” cadenza, the big one that even Rachmaninov had found too difficult and had substituted with a shorter, simpler passage that nearly every other pianist adopted.

During the third movement, tensions rose further, and everyone was completely transfixed. When the concerto ended, the audience stood as one. Ignoring the regulations, even the jury stood up and applauded. Richter was crying. Van Cliburn was showered with flowers and gifts, and groups of students set up a chant of “First Prize!” even though six of the nine finalists were still to play.

When the applause showed no sign of letting up, the judges hastily consulted and agreed on a blatant violation of the rules. Gilels took the young American by the hand, led him out on stage a second time, and kissed him in full view of the entire audience.

Across the country, millions of Soviets had gathered in front of their televisions, to watch the broadcast of “Vanya”- the first American that most of them had ever seen live on television.

The standing ovation lasted almost 10 minutes. When the stage was finally reset for the night´s second finalist, Soviet pianist Eddik Miansarov, a large part of the audience had already walked out.

Outside in front of the hall, the police and military cordons collapsed, as fans climbed up fire escapes and across roofs, only to catch a glimpse of their hero, Van Cliburn.

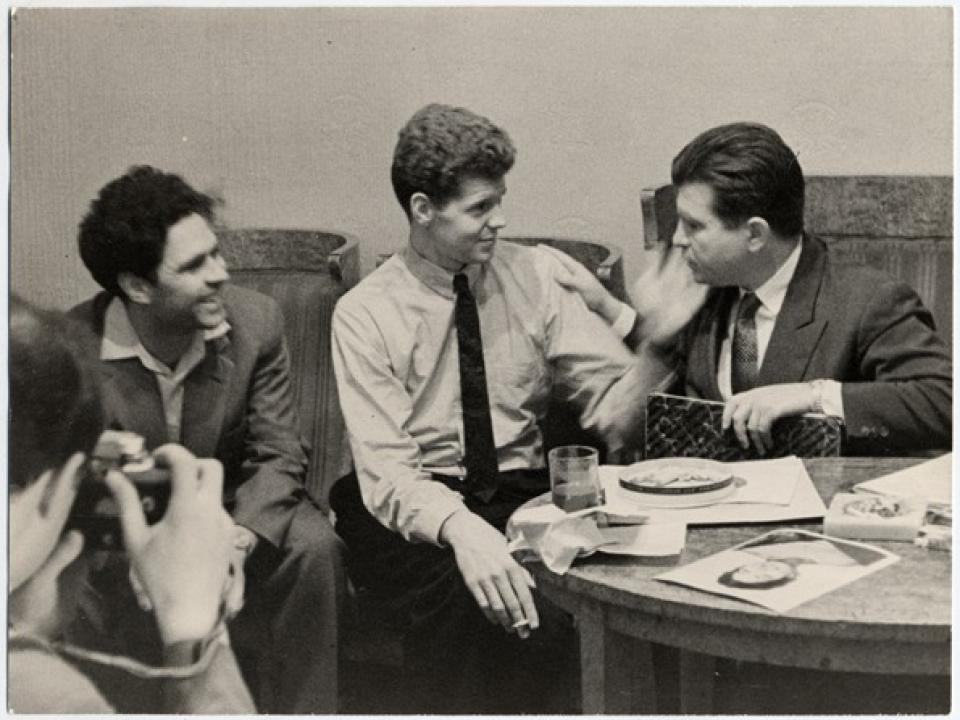

Max Frankel, Moscow correspondent of The New York Times, may have had little experience with the communist system, but that night he got lucky. The moment he saw the pandemonium after Cliburn´s performance, he knew this would become the story of his life. Very late that night, he succeeded in getting his story “A boyish-looking and curly-haired young man from Kilgore, Texas, took musical Moscow by storm tonight” past the censors at Gorky Street, and for once, his New York editors grasped its significance. The story made the morning paper´s front page, along with an artist picture of Van Cliburn.

The significance of his story certainly did not go unnoticed by the Soviets, either. On the day after Cliburn´s triumph, every member of the Central Committee received a secret dispatch from Deputy Culture Minister Kaftanov, recounting the performance, the standing ovation from all members of the jury “contrary to the provisions of the competition” and the audience chant of “First Prize, First Prize!”. Apparently, the foreign jurors, knowing that First Prize was to be given to a Soviet artist, had requested a special “Big Prize” for Van Cliburn, but the rules of the competition did not provide for such a prize.

Other jury members were proposing to share the first prize between Van Cliburn and Lev Vlassenko, but both Kabalevsky and Gilels argued that this would not have been fair and could result in complications, i.e. the foreign members of the jury marking down other Soviet musicians. At the bottom line, the Ministry of Culture reiterated its view that First Prize should be given to Van Cliburn.

While the finals were still ongoing and the two Soviet contestants Vlassenko and Shtarkman had not even played yet, the ministry did not expect any important changes to the situation. It did, however, rightly assume that a Cliburn win would be met with approval from broad circles of the musical public and would raise the authority of the Tchaikovsky Competition. Consequently, the Soviet Culture Ministry, having pressured Lev Vlassenko to take part in the first place, and having selected him as their preferred winner of the competition, demoted him to second place- before he had even played.

Ultimately, the decision was made by Nikita Khrushchev. In the “official” story released to the press, Khrushchev acted instantaneously and decisively: “Was he the best? Then give him the prize!”. In reality, the situation was much more complicated. Early on, Kremlin operatives began to take sides, and the Tchaikovsky situation quickly became a game of influence exercised at the highest levels. Sources close to Emil Gilels said that he called Khrushchev´s Assistant Vladimir Lebedev, hoping to influence the situation through a back channel before reaching out to Ekaterina Furtseva, Secretary of the Central Committee. Gilels apparently argued on behalf of giving the price to Van Cliburn, asserting that “it could end the Cold War, and there will be peace”. Furtseva seemed to agree with Gilels, while others, including the so-called “Black Cardinal” Mikhail Suslov, a Stalin protégé and nationalist politician, strongly opposed the two, arguing that the victory of an American would be an ideological defeat. A compromise in the form of a split First Prize was met with resolute refusal by the Jury. Kabalevsky, the Jury Chair, said that such a decision would be a death sentence for the competition, and that without a written order from the Central Committee he would refuse to vote that way.

In the end, it came to a heated discussion right in front of Khrushchev. But as the nationalists tried to force a decision in their favour, Khrushchev had apparently already made up his mind: “As the jury is insisting on it, we do not need to interfere. They are professionals. And having an American win is even good, we will show the world our impartiality” wrote Khrushchev´s son Sergei about the encounter. Khruschev added: “The future success of this competition lies in one thing: the justice that the jury gives”.

And thus, Van Cliburn was officially declared winner of the First International Tchaikovsky Competition, on 13 April 1958.

While this decision certainly marked a turn-around in Soviet politics, it was not the only one related to the Tchaikovsky Competition. The chairman of the steering committee of the competition was Dmitri Shostakovich, a “mercenary formalist” and declared “enemy of the people”. As the competition was attended by foreign artists and press from all over the world, the regime got worried that someone might question the authorities´official stance on the great composer, who had been denounced (for the second time in his life) in 1948, and was still not fully rehabilitated. And so, on 22 April 1958, Lenin´s birthday, Shostakovich was given the Lenin Prize, one of the most prestigious awards of the Soviet Union. Galina Vishnevskaya remembers: “The First Tchaikovsky Competition went swimmingly, except the fact that the American Van Cliburn came from nowhere and took the first prize in piano. Shaken by the occasion, a government delegation, headed by Khrushchev, appeared at the final concert. I believe it was the first and last time that officials of the Soviet government visited a hall of the conservatory. The box seats intended for them are always empty; but the tickets are never sold to anyone else. I suppose everyone is hoping that that the leaders suddenly will develop a thirst for high art and turn out for some symphony concert. I cannot remember that they every came, except for that one time. They came to look at “Vanya”, the tall, lanky American who had beat out all the Soviet pianists and become the public´s idol- to whom, after his performance, they presented vodka, balalaikas, and pies.

Shostakovich, as chairman of the steering committee, handed out the awards, and the young foreigners were delirious with joy to see Shostakovich in the flesh and to have the honor of shaking hands with him. At that moment it must have become clear to our hotheaded leaders that they were caught in an indecent situation. There they were in the audience applauding and honoring Dmitri Shostakovich along with the rest- paying tribute to a great composer of the twentieth century, whom the Soviet regime had not quite finished off. They had long forgotten what he had been persecuted for- well, it hadn´t been to death, had it? The result was that one morning a month later we read in the newspaper a government decree entitled “On Correcting Mistakes Made in Evaluating the Work of Leading Soviet Composers”. Our leaders, thoroughly plagued by awkward questions put to them by Western intellectuals, were obliged to admit that they had been wrong to persecute their own musicians- that it was something without precedent in world culture. If it had not been for the Tchaikovsky Competition, I am convinced that the decree would never been issued”.

©WFIMC 2022/FR

Sources:

Stuart Isacoff: When the World Stopped to Listen (Knopf Doubleday)

Nigel Cliff: Moscow Nights (Harper Collins)

Galina Vishnevskaya: Galina. A Russian Story, 1984 (Harcourt Brace Jovanovic)