WFIMC: You were born in Bucharest and grew up with the name “George Enescu” all around you. What are your earliest memories of the Enescu Competition?

Mihaela Martin: My first memories go back to the early 1970s, when I was around 12 or 13. I was a pupil at the music school, and my violin teacher took me to practically every session. I remember it as the first time in my life that I heard so much Bach being played in such a concentrated way. For a twelve‑year‑old, that was overwhelming—in the best sense.

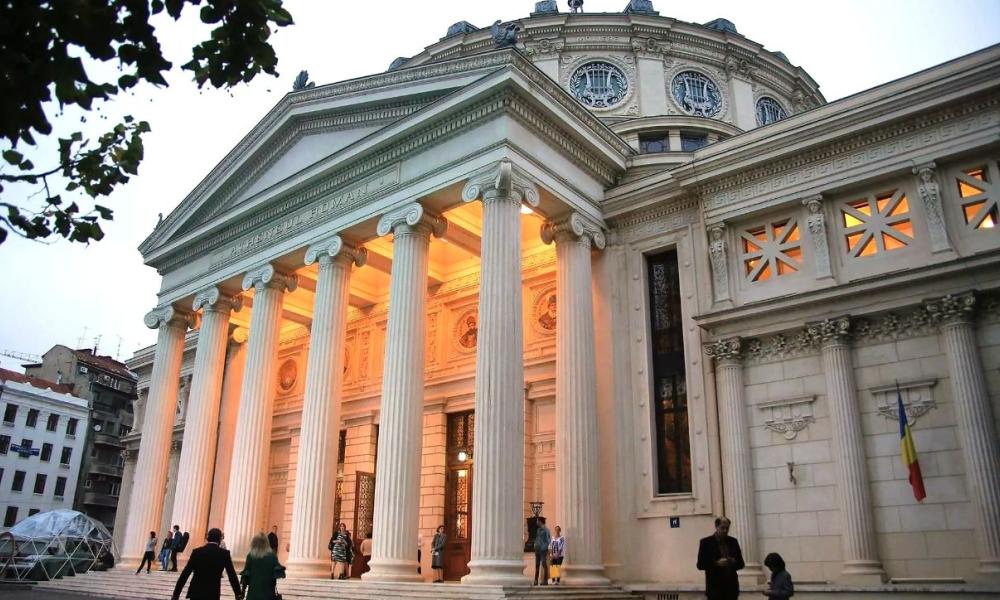

The hall was always completely packed, especially for the finals. There was an atmosphere of real celebration, almost like a feast of music: new faces, new discoveries, international artists coming to Romania and playing at the highest level. I remember running after the competitors with my booklet, asking for autographs. For me then, the competition was not just a musical event; it was a revelation.

Today, of course, I see it from a different perspective, as a jury member and as someone who has had a long career. But each time I walk into the same halls, there is something deeply familiar. The architecture is the same, the smell is the same—there is a continuity there that I cherish.

For a young Romanian musician in those days, what did the Enescu Competition represent?

It was a window to the world. Romania was behind the Iron Curtain, yet for those few weeks you had the sense that the world was coming to you. I remember, for example, the year when Sylvia Marcovici won first prize, or when Philippe Hirschhorn participated.

Sylvia was already an important soloist, but she still taught privately, and I was very lucky to be one of her pupils. She spoke about this “very good violinist” who was coming—Hirschhorn, who had just won the Queen Elisabeth Competition. Nobody understood why he would come to Enescu after Queen Elisabeth. But I still remember his performance to this day: an incredible combination of beauty, electricity and depth.

The competition was really international even back then: many European musicians, including some from France, and at least a few from Japan. There were fewer Asian participants than today, of course, but for us, any foreign competitor was a door opening to another world.