Artists and the Almighty Power of the State

Where Music ends and Politics begin- then and now

By Florian Riem

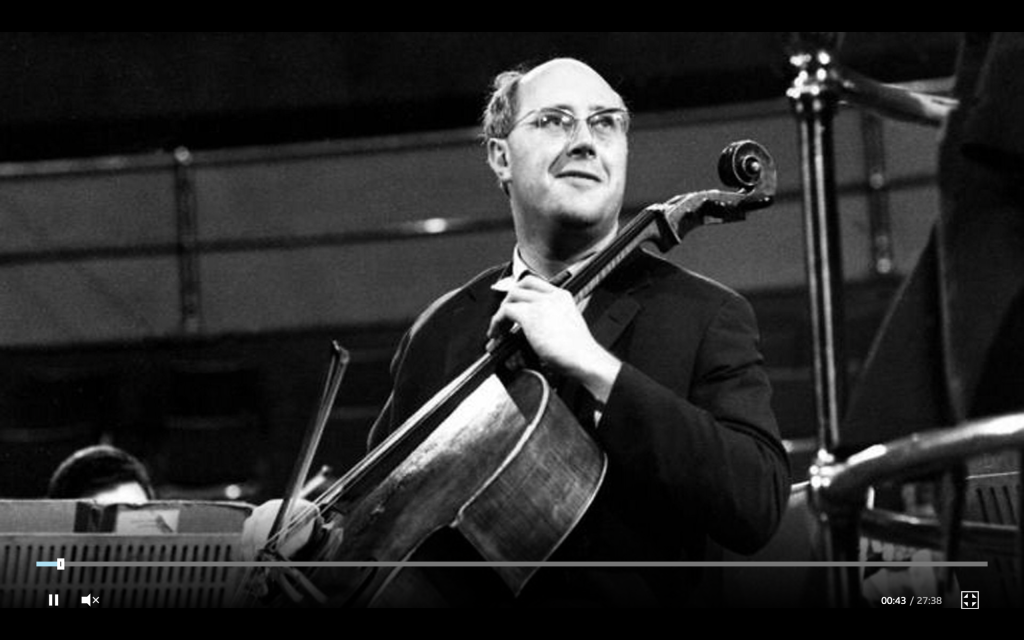

It was no ordinary day for the BBC Proms, when the State Symphony Orchestra of the USSR, Yevgeny Svetlanov and Mstislav Rostropovich took to the stage on 21 August, 1968. Following protests outside of the hall, heckling and skirmishes began in the audience before the concert even started. “Russians out!” and angry calls for the performance to be cancelled made it almost impossible for the musicians to start the concert.

The rage of the audience came to no surprise. Overnight, the Soviet Union and its allies had invaded Czechoslovakia, sending thousands of soldiers and tanks into the country to stop the Prague Spring and to crush the lenient rule of Alexander Dubcek.

Rostropovich somehow saved the performance. With the greatest irony, the work he was scheduled to perform was the Czech composer Antonin Dvorak´s Cello Concerto. As Julian Lloyd Webber recounts:

"I was there: the extraordinary intensity of Rostropovich´s performance, together with the tears visibly pouring down his cheecks as the concerto neared its end, spoke more than any number of words”.

You can listen to this historical performance of Rostropovich playing Dvorak at the 1968 BBC Proms HERE

More than 50 years later, we find ourselves in a similar situation. Russia has invaded Ukraine, and the much of the world is responding with a blanket ban on everything Russian.

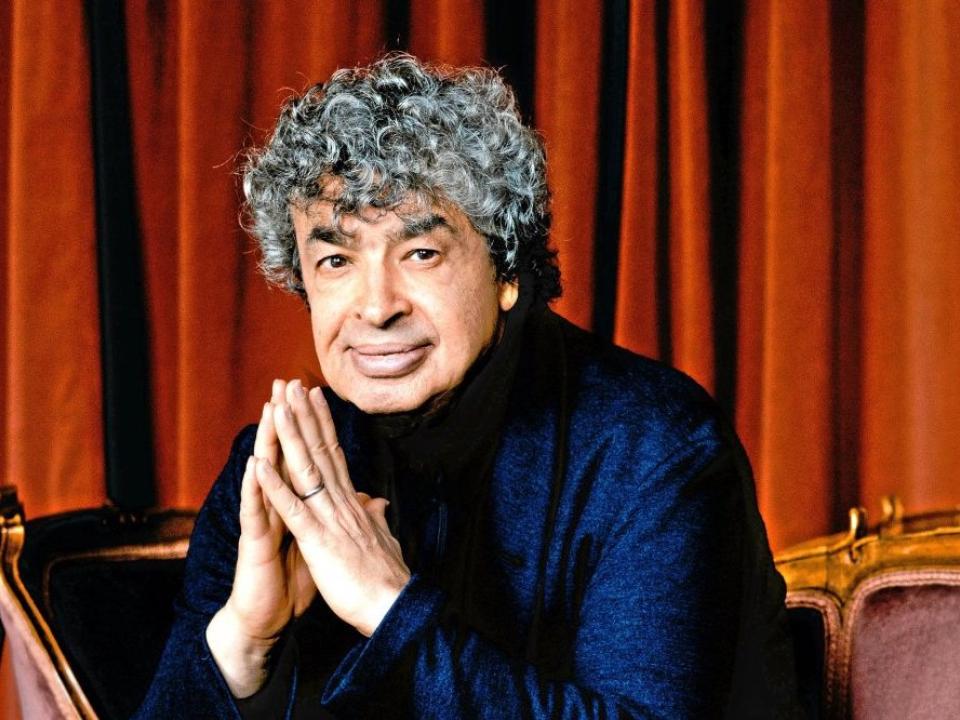

Maybe the most prominent among the artists being banned from the west, conductor Valery Gergiev, is a known ally and supporter of Vladimir Putin. He has appeared in his election campaign and served Putin´s propaganda on numerous occasions, like the cynical “liberation” concert in the ruins of Palmyra. He has also clearly supported Putin´s annexation of Crimea. This of course has been known all along, and we have accepted it- until now, until the beginning of Russia´s war in Ukraine.

„…when we speak about those who are aligned with the regime, who have benefited from it in every possible way, from social status and honours, financial privileges, and sponsorship from State-aligned companies, well — they have to declare their position. If they are in favour of this war then I don’t think I want to hear what they express in art — because for me art is not about that. It’s about spirituality — that means to sustain people, not to bring them down. And with that comes a certain responsibility.“ Semyon Bychkov

But with countless other Russian musicians, composers, writers, the issue becomes much more complicated. Tchaikovsky, Rachmaninov, Mussorgsky, Prokofiev, Shostakovich and many more count among the world’s most loved composers. Are we now to refuse them just because they were Russians? And if we did, what would make us different from, say, the Germans burning books and forbidding music that did not serve their racial prejudice or political ideology?

Less than a century ago, German artists- conductors, performers and composers alike- were being instrumentalized and used for propaganda by a genocidal regime. Wilhelm Furtwengler, Eugen Jochum, Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, Richard Strauss, Carl Orff and many others kept performing while their Jewish counterparts were persecuted or had to leave the country. After the Second World War, their image was tarnished, and their political involvement affected their reputation, some of them more than others.

„Declarations about war and politics are not fitting for an artist, who must give his attention to his creations and his works.“

Richard Strauss (Richard Strauss and Romain Rolland, Calder and Boyars, London, 1989)

In 1914, Richard Strauss refused to sign the Manifesto of German artists and intellectuals supporting the German role in the war. (According to many, Strauss was completely apolitical, however his acceptance of the role as President of the Reichsmusikkammer from 1933-1935 made him an official representative of the Nazi government).

Little has changed since then. In 2014, exactly one hundred years later, more than 500 Russian artists signed a letter supporting Russia´s annexation of Crimea. Among the signatories, Yuri Bashmet, Valery Gergiev, Denis Matsuyev, Vladimir Spivakov and many other important figures.

When it comes to music competitions, their political value can be quite important as well. After Soviet pianist Lev Oborin won the first International Frederic Chopin Competition in 1927, the Soviet regime was quick to emphasize the high level of culture and education in the USSR and began to pay increased attention to its strategy of selecting competitors.

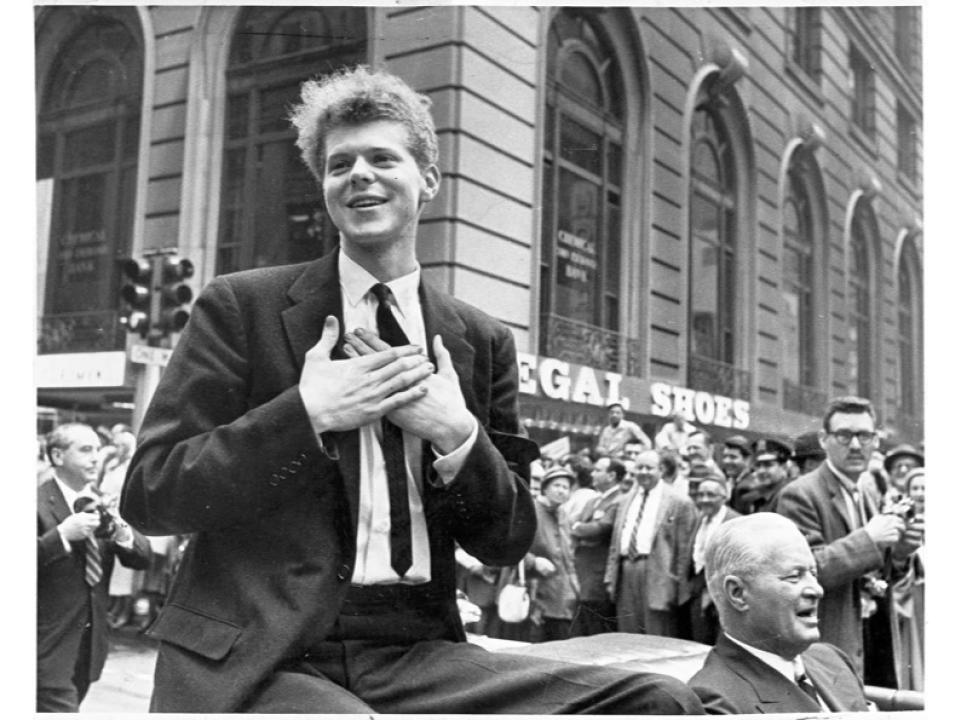

On the other side of the world, Texan pianist Van Cliburn became a national hero in the United States after winning the first International Tchaikovsky Competition in 1958. He had studied with the Russian exile pianist Rosina Lhévinne at the Juilliard School in New York.

Today, things are somewhat different. State control of music making in Putin´s Russia cannot really be compared with Nazi Germany or the Soviet Union. Artists do not necessarily „represent“ their country like in a sports contest. Still, the chances for those still in Russia to speak out and voice an opinion against the government are already very limited and will likely become even more so.

With all this in mind, the World Federation of International Music Competitions has distanced itself from the International Tchaikovsky Competition, an institution directly run by the Russian regime. But at the same time, it has opposed a blanket ban on Russian artists and Russian candidates- from the beginning of this war. This will not be easy. Graphic images from the war, growing public sentiment and with it the ever present social media can easily make us forget that there are others. Ordinary people speaking out, protesting against their government, knowing they may be punished and even arrested. People who do not betray their conscience, their values; people who do not remain silent in the face of violence and destruction.

Today, it is essential for the west to keep the door open. Consensus and dialogue must prevail over separation and confrontation. The war in Ukraine will not end tomorrow, and finding a way back to even a relative normality will take a long time. Cancelling Russian music and shutting out Russian musicians will not bring help and support to the people suffering in Ukraine. Therefore, it is even more important to keep relations to the other side of the border alive. Where else can we find common values, where else do we have a common understanding if not in culture? In times of war, culture bears a special responsibility. We trust our colleagues „on the other side“, and they trust us. We will need them, and they will need us. We need this dialogue today as much as we will need it in the future- for the generations yet to come.

©WFIMC 2022