1919- Year of Destiny

Ignacy Jan Paderewski and Polands Road To Freedom

By Florian Riem

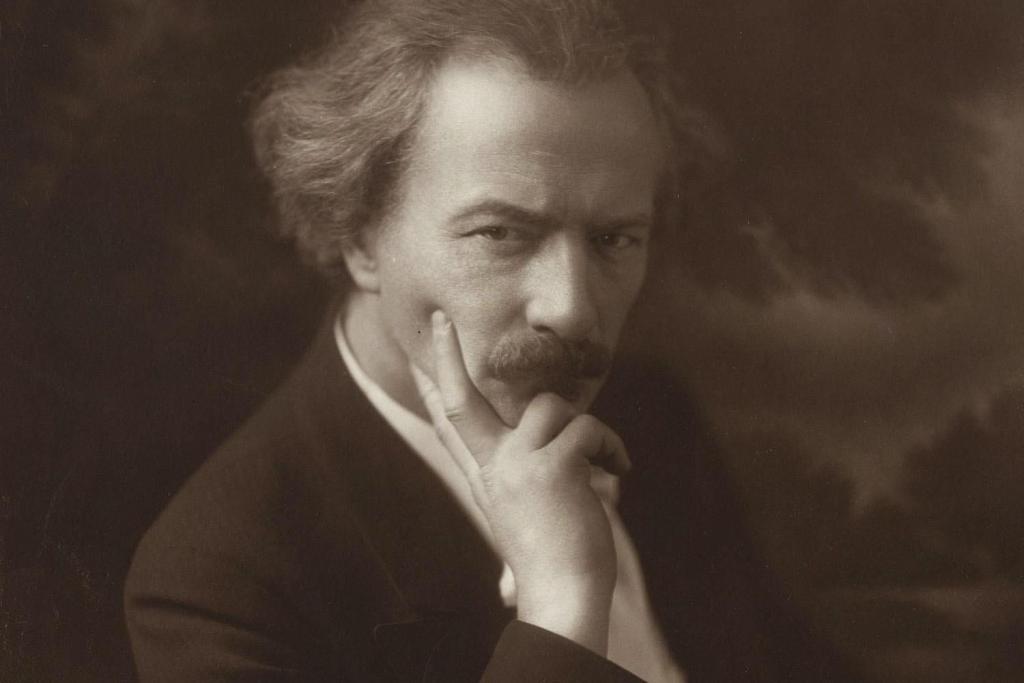

Paris, 18 January 1919. Ignacy Jan Paderewski, named Prime Minister of the Republic of Poland a mere three days before, visited the Quay d´Orsay on his first official trip abroad. “So you are the famous pianist?” asked the French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau, shaking Paderewski´s hand in admiration. "And you allowed them to name you Prime Minister of Poland? Oh! What a downfall!”

Paderewski was a pianist, composer, teacher, but also a philanthropist, diplomat, and first and foremost a great patriot. Using his charme and moderation, he was able to resolve countless conflicts and smooth out a great many problems on his political agenda. For the victors of World War I, Ignacy Paderewski was the only person capable of forming a National Union Government. A world-renown pianist, Paderewski had no prior political experience aside from his activities in the Polish resistance. But his voice was heard by world leaders: US President Woodrow Wilson had met Paderewski as representative of the Polish National Committee and later included in his famous peace plan for Europe the creation of an independent Polish state- a huge accomplishment for the young republic.

Ignacy Jan Paderewski was born on 6 November 1860 in Kurylówka, Podolia, a town occupied by Russia at the time but situated in Ukraine today. Despite his fairly wealthy parents, he faced a childhood of hardships: his mother died only few months after giving birth, and his father was arrested in connection with the January Uprising in 1863. After some initial piano lessons, Paderewski applied for studies at the Warsaw Conservatory- at age 12! Thanks to the impressive sketches of his youthful composition book, he was accepted without any examinations. Six years later, he graduated and was offered a teaching position at his school. In 1881 he moved to Berlin for further studies in composition, followed by a few years in Vienna, where he studied piano in the masterclass of the famous Theodor Leschetizky, and where he later gave a celebrated debut as pianist.

Soon, Paderewski enjoyed a growing popularity. His debut recitals in Paris (1889) and London (1890) made him an international star, admired and adored by an enthusiastic, sometimes fanatical audience. His first recital in Paris at Salle Erard on 3 March, 1889, was attended by Gounod, Massenet, Saint-Saens as well as Tchaikovsky. Alfred Cortot, who was 12 at the time, later remembered the performance: “He appeared with the suddenness of a lightning stroke, making a blurring, an eruption in our hearts. Instead of a pianist, an inspired poet took possession of the keyboard.”.

Paderewski was also rather well known as a composer. Besides his symphony Polonia, his Piano Concerto in A Minor, and his opera Manru, his Minuet from Six Concert Humoresques Op. 14, written in 1887, sold millions of copies during his lifetime, was recorded by acclaimed pianists (among whom Rachmaninov and Paderewski himself) and transcribed for several instruments (including for violin by Fritz Kreisler and for cello by Gaspar Cassadó).

The Second Liszt

"His playing is unparalleled, original, unique », praise Lausanne newspapers after a concert given by Paderewski on 21 December 1889, dedicated to Saint-Saëns, Liszt and Chopin. « The mere activation of the two pedals enables him to obtain previously undiscovered effects; he plays to the instrument’s full scale of sound, touch and expression with incredible confidence and skill. His fortissimi challenge the entire orchestra, resounding like thunder, then instantly shifting to piano and pianissimo with startling dexterity.“

(Musee Paderewski, Morges)

Another witness of his first successes was Queen Victoria of Great Britain, who wrote in her 1891 diary: “Went to the green drawing room and heard Monsieur Paderewski play on the piano. He does so quite marvelously, such power and such tender feeling. I really think he is quite equal to Rubinstein. He is young, about 28, with a sort of aureole of red hair standing out.”

For Paderewski, the world suddenly seemed wide open. When in 1891 the piano maker Steinway and Sons offered him a contract for eighty concerts in the United States along with a guarantee of $30,000, he did not hesitate. On 3 November, 1891, Paderewski sailed for New York. It would not be his only trip: he would tour the country more than 30 times during the following decades. His charisma and stage presence along with his striking looks became emblematic for the highest level of piano virtuosity. But public admiration of Ignacy Jan Paderewski also manifested itself in its most extreme, with displays of wild enthusiasm at the sight of the artist and huge media interest in his personal life. Some fans even believed he possessed supernatural powers. The term “Paddymania" was coined in America, where he was referred to as Paddyroosky or simply Paddy.

While numerous tours firmly cemented his worldwide reputation, they also provided opportunities to meet people who later turned out to be of the greatest importance for his political endeavours. One day after a concert in Kansas City, he recognised a lady backstage as a former Leschetizky pupil. Delighted to see her, he did not hesitate to accept her request to teach one of her students. This particular student was a talented boy but nevertheless decided later to give up a career in music in order to move on to other things. His name was Harry S. Truman... Little did they know that on this night in Kansas City, the future Prime Minister of Poland had just given a piano lesson to the future President of the United States.

Back in Europe, an event occurred that was both important in itself and of great significance for Paderewski: 1910 marked the 500th anniversary of the Battle of Grunwald: On 15 July 1410, a victorious Polish army had decisively defeated the German Teutonic Order in what was one of the largest battles in medieval Europe. Among 150.000 people celebrating this anniversary in Cracow, Paderewski gave a prophetic address, foreseeing the war that would soon engulf the entire world: “Brothers, the hour of our freedom draws near. In the next five years, a fratricidal war will plunge the whole world into a blood bath. Be prepared, my fellow countrymen, Polish brothers, be prepared! Because out of the ashes of burned down and destroyed towns, villages and houses, from the dust of this tortured land, the Polish Phoenix will be born again!

Another anniversary occurred that same year: the centenary of the birth of Frédéric Chopin. Paderewski´s address, held in Lwów on 23 October 1910, became legendary as it seemed to mirror the quintessence of the Polish soul:

Chopin was a musician; and music alone, perhaps his music alone, could reveal the fluidity of our feelings, their frequent overflowing towards infinity, their heroic concentrations, their frenzied ecstasies that would move mountains, their impotent despair, in which thought darkens and the very desire of action perishes. This music, tender and tempestuous, tranquil and passionate, heart-rending, potent, overwhelming: this music which eludes metrical discipline, rejects the fetters of rhythmic rule, and refuses submission to the metronome as if it were the yoke of some hated government: this music bids us hear, know, and realise that our nation, our land, the whole of Poland, lives, feels, and moves, in tempo rubato.

(Fryderyk Chopin, A Discourse, 1910)

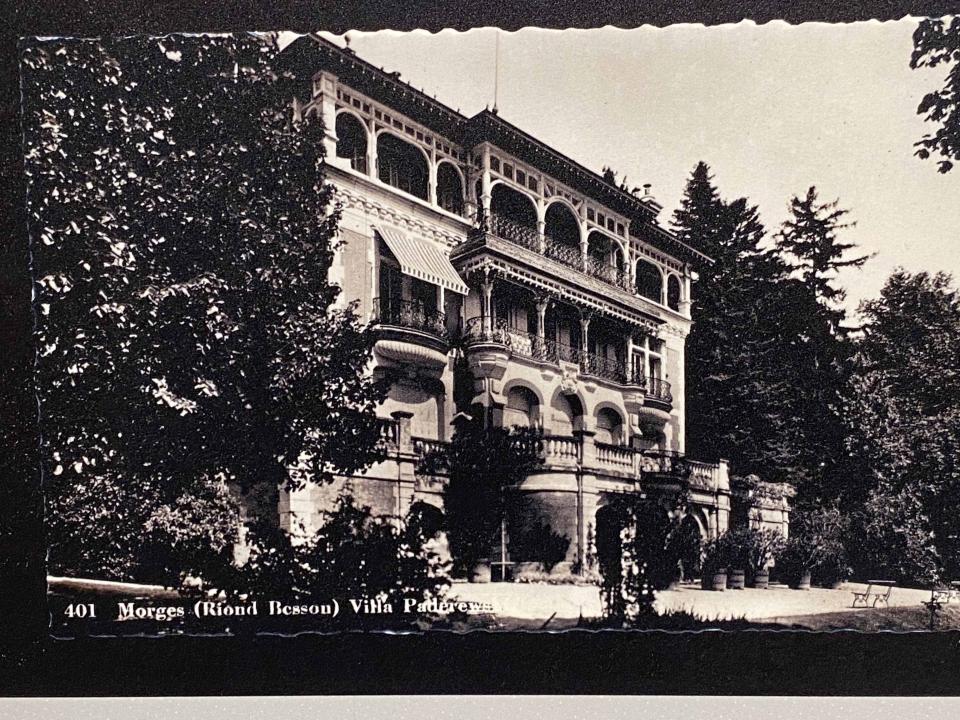

Back in 1897, Paderewski had taken up residence at Riond-Bosson, near the town of Morges, Switzerland. The legendary lakeside property, part chalet and part Venetian palace, was surrounded by a vast estate and should remain his home until 1940. Breathtaking vistas of Lake Geneva and backdrop of the Swiss alps added to the magic of the place, where Paderewski hosted guests from all over the world.

I was struck first by the two concert grands with their keyboards facing each other, lined up along two bay windows. [...] Both pianos were covered with flowers and framed photographs of kings and queens, Spanish infantas, and prominent aristocrats. I noticed also one or two prominent Americans, but, to my astonishment, no Poles.

Arthur Rubinstein, “My Young Years" (New York, Alfred A. Knopf, 1973)

When World War I started in Summer 1914, Paderewski began to organise a relief committee for the Polish victims of war. A highly complex task, considering that 3 million Polish soldiers went to the war, mobilised within the armies of the three empires, finding themselves face to face on the battlefield.

In Warsaw, a Polish National Committee was founded by the National Democrat Roman Dmowski, which laid the foundations of a future Polish State. Installed in Paris, and later in Lausanne, this “government in exile” was represented by Paderewski in the United States.

Paderewski returned to America in January of 1915 and immediately began to raise money to aid the war relief in Poland. His wife was equally active and began selling dolls in traditional Polish costumes all over the country, at 5 dollars each, under the banner of the American National Committee of the Polish Victims´Relief fund. Named "Jan and Halka” some were dressed in 1918 in the uniform of the Polish White Cross nurses, founded by Helena Paderewska herself, in order to encourage young Polish women in America to serve.

At the same time, Paderewski quietly began to look for contacts to the American government. “The first direct evidence of his capacity as a leader which impressed me,” wrote the US Secretary of State, Robert Lansing, “was his successful efforts to unite the jealous and bickering Polish factions in the United States.... I am convinced that Mr. Paderewski was the only Pole who could have overcome this menace.... His entire freedom from personal ambition made him the one man about whom the Poles, regardless of factions, appeared to be willing to rally. It was a great achievement, a triumph of personality.”

In the summer of 1916, Paderewski was invited to a diplomatic dinner at the White House, where he met President Woodrow Wilson for the first time. And although Wilson did not know much about music, it did not take any special knowledge to get the message that this Polish artist was trying to convey by means of Chopin’s music.

In 1917, President Wilson addressed Congress on “Essential Terms of Peace in Europe” and for the first time mentioned an independent Poland: "I take it for granted ... that statesmen everywhere are agreed that there should be a united, independent, and autonomous Poland, and that henceforth inviolable security of life and worship ... should be guaranteed to all people who have lived hitherto under the power of governments devoted to a faith and purpose hostile to their own."

When America declared war against Germany and President Wilson ordered a full mobilization, Paderewski did not stand back. He addressed the “Union of Polish Falcons”, the most important Polish-American group, and called for the formation of a separate Polish army, to fight side by side with the Allies. An unimaginable task for a pianist… but Paderewski won his point and prevailed, convincing the French and American governments to let him go ahead with his plans for the formation of the army. Two training camps were founded, and twenty-two thousand Polish-Americans volunteers were sent to the Western European front, backed by the benevolence of doctors and nurses of the Polish White Cross.

During the war, Paderewski also helped his countrymen in America: when Poles of Austrian and German origin found themselves in a difficult position in the United States, Paderewski obtained from the American government the authorisation to set up and agency responsible for identifying these Poles and giving them certificates of nationality.

For all these efforts, the Polish army paid tribute to Paderewski in a superb and moving way. His name was inscribed on the name list of each company. Every day at roll call, when the name “Ignace Jan Paderewski” was read, thousands of voices shouted back, “Present!” This honor had been paid to a soldier only once before in history—to Napoleon. It had never before been paid to a civilian.

In November 1918, when the war came to an end and the cannons finally fell silent, the situation was extremely chaotic in Poland, and the danger of a civil war was very real, particularly between the armies of Generals Haller and Pilsudski. The allies considered Paderewski the only figure capable of preventing such a war and offered him their help. “We have every confidence in you and we believe that your presence will prevent bloodshed” declared the British Foreign Secretary, Arthur Balfour. Thus, Paderewski left New York on 23 November 1918 for London, before embarking on a Royal Navy warship headed for Gdansk, Poland.

Christmas Day, 25 December 1918: a triumphal welcome awaited Paderewski in Gdansk, which at the time was still occupied German territory. Moving on to Bydgoszcz and Poznan, he finally arrived in Warsaw on New Year’s day 1919 and settled in the Bristol Hotel. The people´s welcome was delirious, but his country was in ruins. The political differences between left and right, between the de-facto Chief of State Józef Pilsudski and Roman Dmowski, the chief of the Polish National Committee, Poland´s representative in Paris, seemed insurmountable. Yet, with considerable assertiveness as well as with the help of the American mission in Warsaw, Paderewski managed to succeed. On 15 January, he was summoned, albeit reluctantly, by Pilsudski to form a national union government- within 48 hours. Paderewski himself was named Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs, and the first free parliamentary elections in 140 years were held six days later.

When Paderewski finally reached Paris, the Peace Conference was in its eleventh week. Paderewski realised that his unavoidable delay in Poland had been a costly one, and everything seemed already settled- to the disadvantage of Poland. But once again, he managed to turn things around. “He came to Paris,” the American Colonel Edward House later wrote, “in the minds of many as an incongruous figure, whose place was on the concert stage, and not as one to be reckoned with in the settlement of a torn and distracted world. He left Paris, in the minds of his colleagues, a statesman, an incomparable orator, a linguist, and one who had the history of Europe better in hand than any of his brilliant associates.”

Paderewski´s success was not all he had envisioned. But it was more than anyone could have hoped for. The establishment of Poland as a nation, free and independent among the nations of the world—this was the major issue, and this was finally brought about on 28 June 1919, when the Treaty of Versailles was at last presented to the delegates for their signatures. US Secretary of State Robert Lansing later remembered this moment and wrote: “Paderewki´s achievements as a patriot and statesman, and his magnificent genius as a master of harmony, have won the applause of an admiring world and made his name immortal”.