In the spring and summer of 1938, the ten-year-old Hellmut Stern still experienced moments of adventure: While his parents thought he was at school, he explored parts of Berlin on his own. However, the November Pogrom of 1938 (Kristallnacht) brought this time of relative freedom to a definitive end. Jewish shops were looted and destroyed, and synagogues and schools were burned. Students and teachers alike were pelted with stones by members of the Hitler Youth.

Soon after the Nazis came to power in 1933, the family had sought opportunities to emigrate, first to Palestine, then to countries "all over the world," including to the USA. But nearly everywhere, strict immigration policies were in place, and it became increasingly difficult to escape.

"I still remember how my parents sent out immigration applications all over the world. Every morning when the postman came, there was excitement. I would run to meet him because I wanted to be the first—partly because of the beautiful stamps from all sorts of countries, like Uruguay or Venezuela. I always wanted to read the letters aloud. (…) My father would grow impatient, snatch the letter from my hands, and—yet another rejection! These repeated disappointments left a deep impression on me."

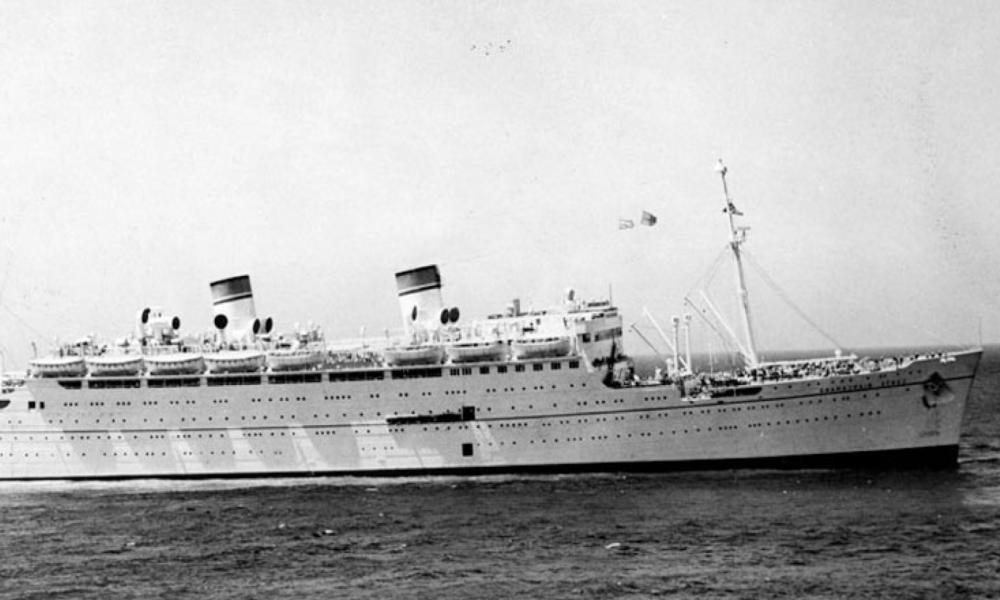

The Sterns also lacked the financial means to emigrate, as they had barely any income since 1933. Finally, Ilse Stern obtained a fictitious contract stating she could work as a pianist in Harbin, China. This was enough to secure a visa for her and the family. The journey almost didn’t happen because the Sterns couldn’t afford the travel costs, but at the last moment, thanks to the help of Hellmut’s violin teacher Gerda Bischof, they managed to gather the necessary funds to leave.